The Leeds Library, where I have the privilege to work, is celebrating the 400th anniversary of Leeds’ first charter by asking its members for their 400 favourite books. (Incidentally, the charter was granted by Charles I, who briefly stayed in the place he formally made a town, at the Red Hall on the aptly-named Head Row on his way to London for trial. We knocked the Seventeenth Century Red Hall down in 1961 to make way for the Schofields Centre (with its terrifying/irresistible snake slide), subsequently fatuously re-named The Core, which is now almost itself demolished. So we knocked down a 338-year-old manor house with links to Charles I to make way for a shopping precinct that lasted less than seventy years…and don’t get me started on knocking down half of Eastgate to make way…anyway...)

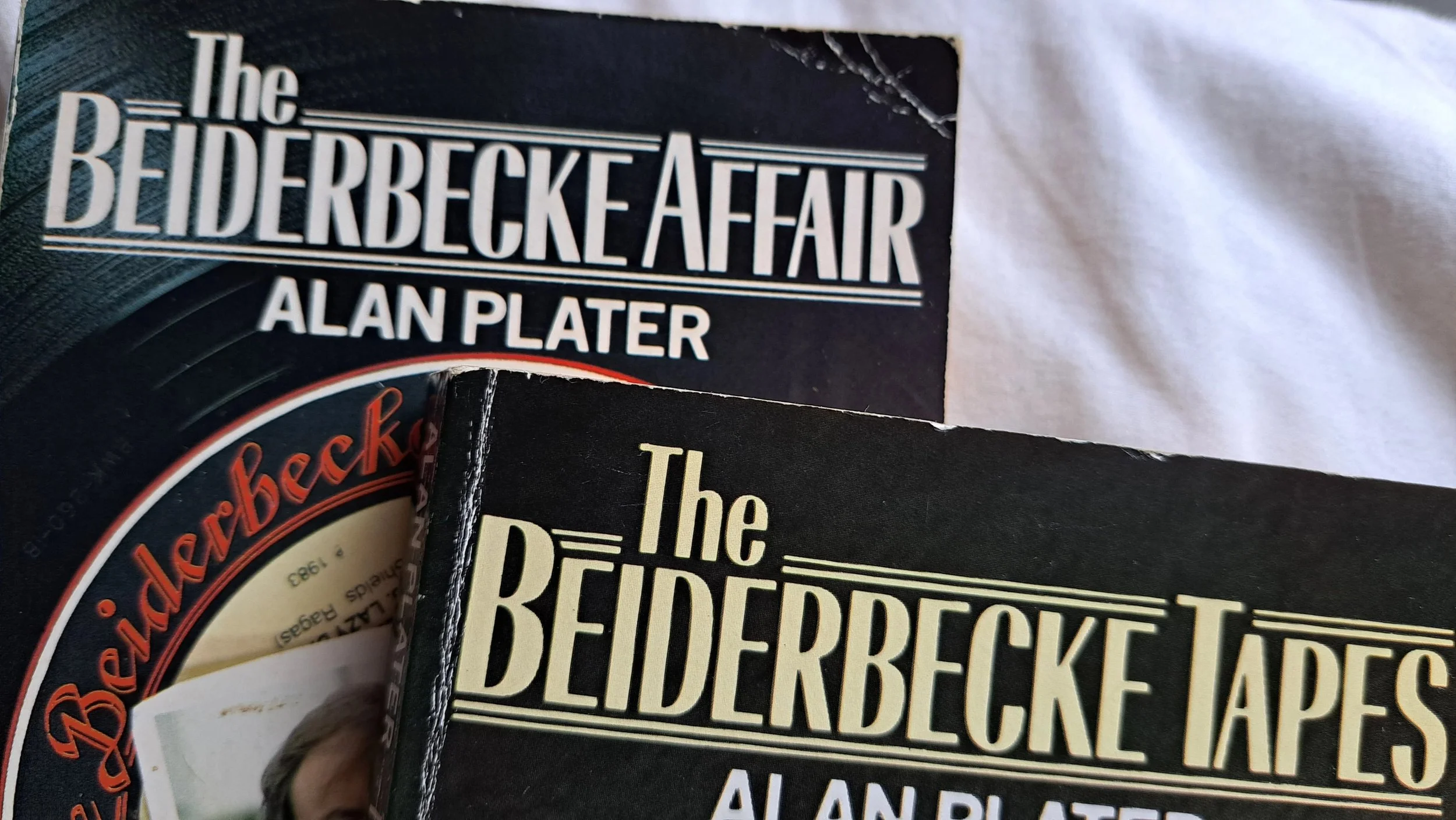

A member of the library, after some inner turmoil, nominated the first Beiderbecke book (‘The Beiderbecke Affair’ by Alan Plater) as a stand-in for the trilogy (followed by‘The Beiderbecke Tapes and ‘The Beiderbecke Connection’). I loved the TV series when I first watched it about fifteen years ago, and after the library member’s recommendation, I picked up two of the three cheaply on abebooks. (The third is a bit more pricey.) The first book came after the first series; the second book came first, and was followed by the TV series. As I rank the TV series so highly, I was pleasantly surprised that Plater had done such a good job translating TV into the book. The second book isn’t as good as the first (it lacks the stand-out characters: Big Al and Little Norm, Sergeant Hobson, Inspector Forrest: “You think I don’t know what a thesis is. Well I do. I’ve got a daughter at a polytechnic and she’s doing one. Great fat bundle of words about sod all.”) but still worth a read, and I’ll be giving the TV series a re-watch at some point soon.

I’ve got a reading coming up at the Albert Poets in Huddersfield on Wednesday 18th February, along with John Duffy, Jeanette Hattersley, and Mike Farren. Last month, it was a lot of fun reading with fellow guest Bob Beagrie, who read (I say read—Bob performed) his brilliant collection ‘Hand of Glory’ from Yaffle Press, a delirious and riotous telling of the adventures of the only known surviving example of a hand of glory at Whitby Museum. Then online, for Explore York Libraries’ Finding the Words with guests Elizabeth Gibson and Alex McCrickard. Finding the Words is monthly, online, and free! Although Pay What You Can donations for the York library service are greatly appreciated. Their next event is on Thursday 19th February at 7:30pm, and features Jill Abram, Aoife Mannix and Joshua Seigal.

What with readings and online sales, I stocked up on copies of ‘Gain Access’. Speaking of which, the Wordsworth Trust, Dove Cottage reading has been re-scheduled for Saturday 11th April at 1:30pm, in person at the Jerwood Centre, Grasmere. Tickets free. This was postponed because of Storm Amy (we’re back at the start of the alphabet—at this rate, it won’t be long til we get to the end…). Happily this time, co-winner Annina Zheng-Hardy will be there in person (she was joining online last year, but can be there in-person for the new date), as will runners-up Sally Baker and Ilse Pedler.

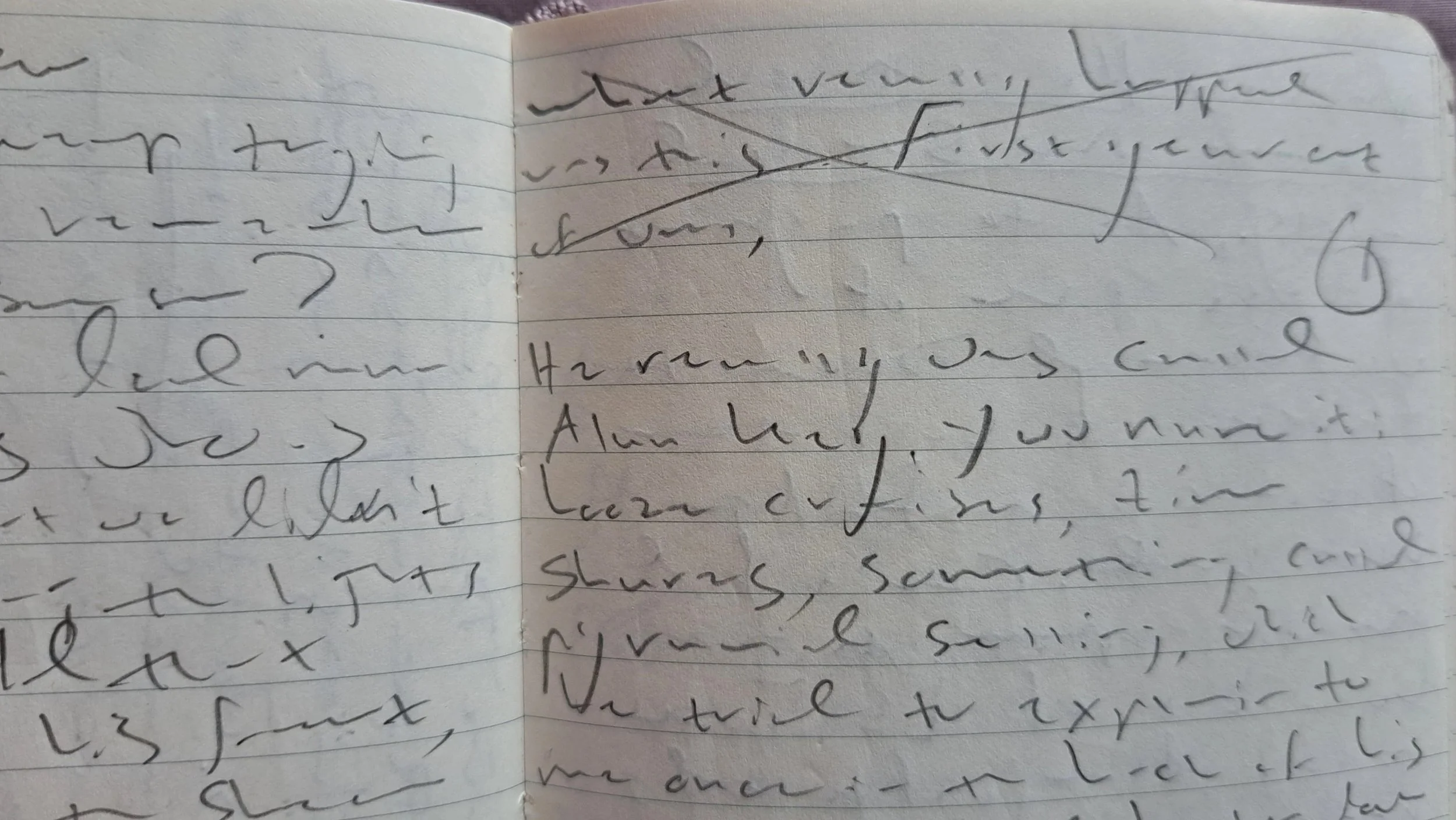

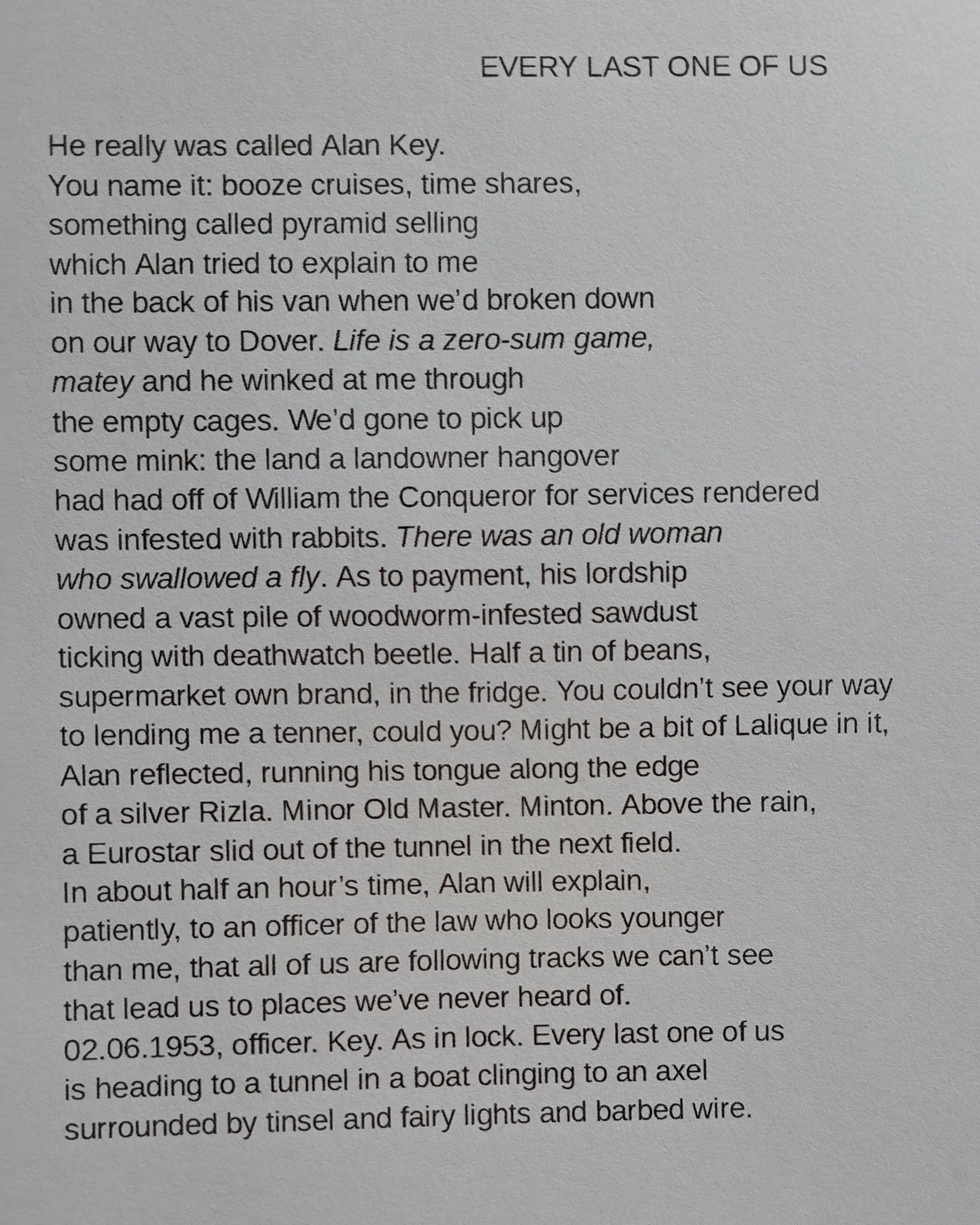

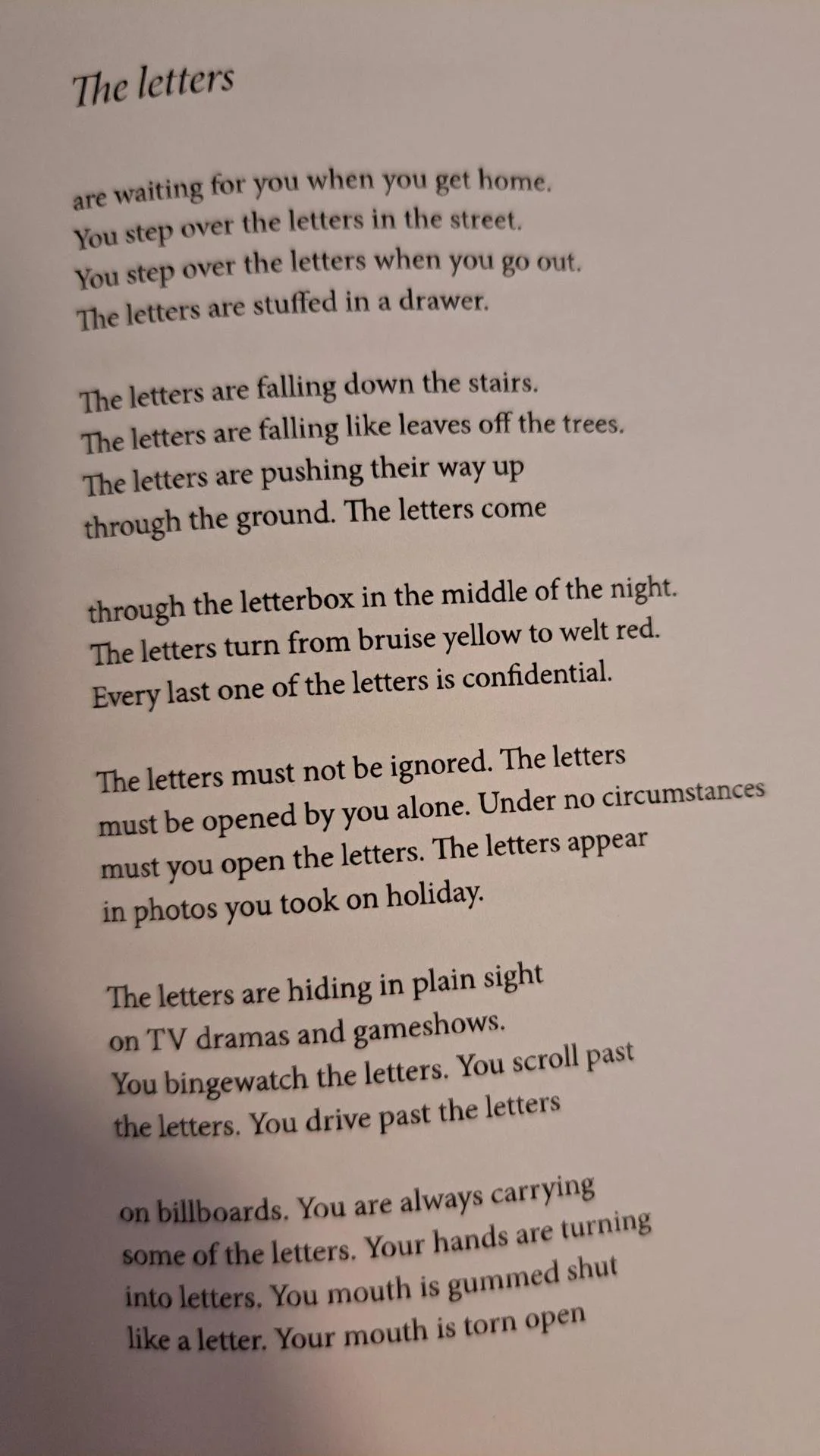

This week, I’ve been working on some hand-made pamphlets. I got into bookbinding after going to a workshop I programmed at the Leeds Library in February last year, run by the fantastic-tutor-and-generally-brilliant Linette from Leeds-based Anachronalia. I can’t recommend her workshops highly enough, especially if, like me, you’re totally new to bookbinding. More workshops with Linette coming up at the Leeds Library later in the year. It seemed logical to use what I’m learning to make some poetry pamphlets. ‘Grow’ is a sequence based on the life-cycle of the cannabis plant; an extended riff on getting stoned. I’m pleased with how they turned out. I’ll have them at readings (50 copies signed and numbered!) and will add them to my shop soon.